Music Reflection: “Wesley’s Theory” by Kendrick Lamar

Through lyrics that describe personal immersion in the struggles of institutional racism and the internal conflicts that arise with mainstream success, Kendrick Lamar Duckworth’s third studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly, delivers a comprehensive narrative of the African-American experience. Released in 2015, the album explores themes of historical prejudice and racist oppression through a blend of self-reflection, sociological analysis, and empowerment. It serves as an outlet to both articulate and challenge the structure of heinous brutality endured by African-Americans both through a modern and historical lens. Widely touted as the magnum opus of Duckworth’s career, the album seemed to launch the reintegration of historical African-American roots into the spectrum of modern hip-hop music culture.

Duckworth’s songwriting talents and sociopolitical commentary presented in the album continue to bolster his international fame and critical recognition; however, his success exists as a byproduct of the turmoil he endured throughout his adolescence in South-Central Los Angeles. Duckworth became immersed in gang culture and substance abuse from an early age, with constant exposures to the injustices of racial discrimination often found in urban working-class communities. The conceptual nature of To Pimp a Butterfly solidified his artistic reputation through a merging of personal anecdotes with historical African-American themes.

This reflection, however, focuses specifically on the album’s opening track, “Wesley’s Theory.” Blending genres of ‘70s funk and soul with modern experimental rap music, the track examines themes of black identity, fame, and American capitalism. Duckworth approaches the status quo of race, culture, and discrimination through a stylistic series of allegories and implicit messages. Regarding the institutional barriers that lessen the likelihood of socioeconomic success for African-Americans, Duckworth encapsulates the central theme of To Pimp a Butterfly with this opening track.

The album’s first track, “Wesley’s Theory,” opens with a brief sample from Boris Gardiner’s “Every N****r is a Star,” in which the crackling sounds of a vinyl record are met with a crescendo of Gardiner repeating the sample track’s title. This seems to introduce the idea of black pride through a reframing of the “n-word,” which diminishes the dehumanizing value of its original meaning when used in this context of empowerment. A spoken-word intro follows, which introduces the overarching theme of the album:

“When the four corners of this cocoon collide, you’ll slip through the cracks hoping that you’ll survive; gather your wit, take a deep look inside; Are you really who they idolize? To pimp a butterfly” (Duckworth et al., 2015).

Duckworth compares the modern African-American social experience to a caterpillar’s metamorphosis into a butterfly, which symbolizes survival and identity enlightenment as a result of transformative experiences. “Pimping a butterfly” essentially translates to a free-thinking African-American individual becoming manipulated and exploited by a system of oppression. This carries a double meaning, however, as “pimping” often carries a negative connotation that relates to glamorized materialism, especially that of African-American culture. The track’s hook follows this theme, as Kendrick expresses how his love for the craft of hip-hop music, referred to as his “first girlfriend,” gradually became corrupted by the temptation of fame and riches:

“Tossed and turned, lesson learned; you was my first girlfriend. Bridges burned, all across the board; destroyed, but what for?” (Duckworth et al., 2015).

In the first verse that follows, Kendrick emphasizes the lavish lifestyles associated with commercial success and the stereotypes of African Americans who achieve high degrees of success. This verse depicts a younger and naive version of Kendrick, who feels invincible after reaching success and relishes in his upcoming fortunes. He states that when he signs his record deal and cashes in, he will purchase expensive cars, attain heaps of jewelry, and supply his home community with weapons. Additionally, he implies that he will inject elements of African-American gang culture into the most revered aspects of white America upon achieving success. He goes on to emphasize the importance of materialism in a capitalist culture and ironically feeds into the irrational fears that racist propaganda perpetuates about young black males in urban cultures:

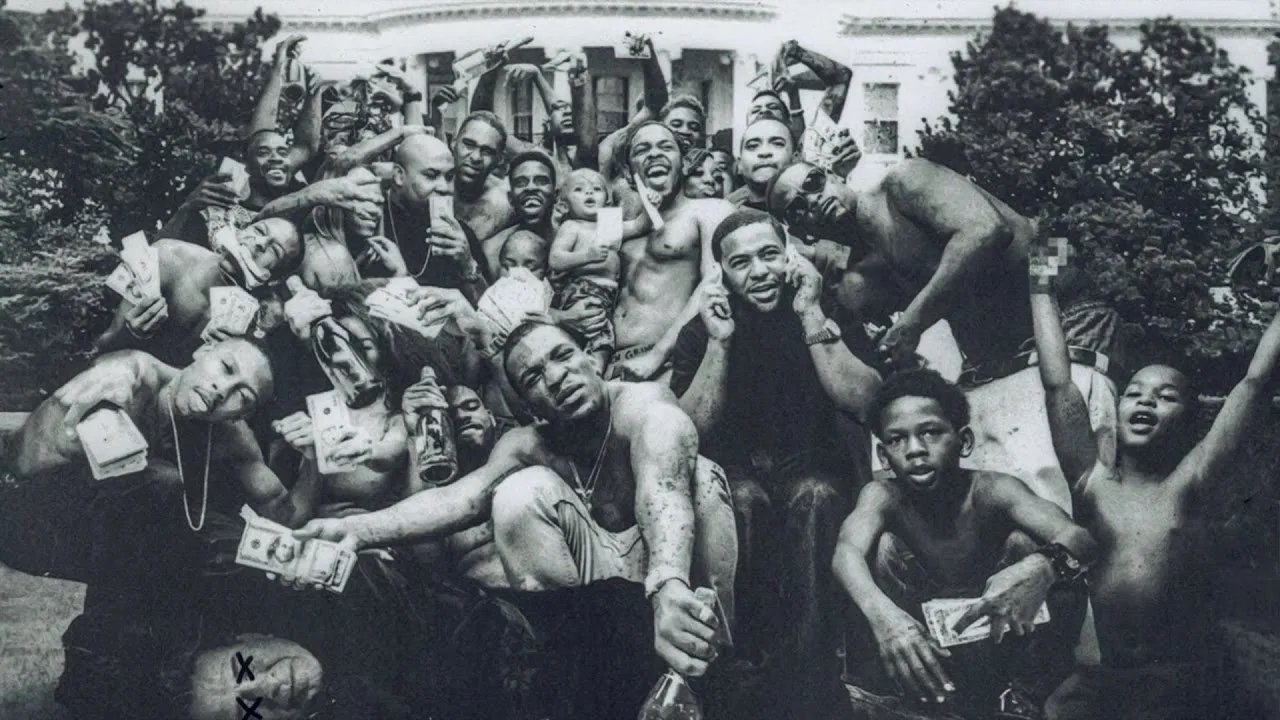

“When I get signed, homie, I'ma buy a strap straight from the CIA, set it on my lap; take a few M-16s to the hood, pass 'em all out on the block, what's good? I'ma put the Compton swap meet by the White House, Republican run up, get socked out; hit the press with a Cuban link on my neck; uneducated, but I got a million-dollar check like that” (Duckworth et al., 2015).

Duckworth dives into the hypocrisy of the “American Dream,” a common theme in African-American history. The ideals of prosperity and independence associated with this concept simply do not apply to the life experiences of the black population due to the history of enforced discrimination. This follows the sentiment felt by black Americans during past periods of wartime, where they felt that any sense of national patriotism would be futile and serve only the best interests of white America.

The illusion of success for black individuals can be seen as another institution created by society to oppress African Americans who wish to escape the unfavorable conditions of their communities. Starting with the Revolutionary Generation, the white-majority institutions of the United States had to shift their methods of control as slavery became abolished. Physical violence and intimidation continue to play a role, but leveraging education over African-American communities achieves less blatant social control. In other words, attempting to coerce African Americans into desiring the glamour of monetary success distracts them from pursuing any form of political influence.

The bridge of the track is met with a voicemail intended for Kendrick from Andre “Dr. Dre” Young, in which he warns Kendrick of the challenges of attaining his success:

“Remember the first time you came out to the house? You said you wanted a spot like mine, but remember, anybody can get it; the hard part is keeping it, motherfucker” (Duckworth, et al., 2015).

Young’s statement directly connects to the track’s title, in reference to the occurrence of actor Wesley Snipes being convicted for tax evasion. Even if such white-collar crimes were committed out of ignorance and with no malicious intent, unjust incarceration continues to plague the African-American experience in the United States. In other words, this acknowledges that the structure of the United States was designed to systematically benefit white populations and marginalize communities of color. Furthermore, this represents the pattern of African Americans not receiving the necessary education or guidance to sustain their economic success. Young perpetuates the mindset of many black Americans during the Reconstruction period that continues to live through many communities as a method of survival - establishing independence to simply become rehumanized after centuries of captivity.

Through Young’s voicemail, Duckworth draws upon the idea of double consciousness, coined by W.E.B. Du Bois, when expressing wariness over attaining his success. Through the lens of an oppressed African American individual, one must be conscious of their public image in the perception of white supremacist America in order to not be subjected to heinous oppression. Because of the historical significance of slavery and its products of discrimination, African Americans must remain hyperaware of their image due to the unjust quality of racial bias in the country’s criminal justice system.

In the second and final verse of “Wesley’s Theory,” Duckworth portrays Uncle Sam, a symbolic personification of American capitalism - an economic system driven by race and class disparities. Duckworth takes a sinister tone to embody Uncle Sam, who calls upon Kendrick to senselessly misuse his fortune on material items and buy products on credit. From an economic standpoint, this serves to benefit financial institutions by forcing individuals into debt, which further maintains the structural racism instilled in social stratification. The persona of Uncle Sam attempts to bait Kendrick with potential desires:

“What you want you? A house or a car? Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar?” (Duckworth et al., 2015).

This references the “plantation generation” of slavery, in which a post-Civil War military order promised forty acres and a mule be granted to freed slaves and their families. Following the outcry of white supremacist Southerners amid the period of Reconstruction, this promise became nullified, securing betrayal as a staple of the African-American experience. Even this promise, given its insignificance when compared to the unprecedented horrors of slavery, could not be fulfilled by the United States government.

The symbol of Uncle Sam, in this context, represents the same values. The closing of the track further emphasizes the manipulation of consumerism through Uncle Sam, by reminding Kendrick that economic prosperity means nothing when compared to education or intellectual influence:

“And when you hit the White House, do you, but remember, you ain’t pass economics in school; and everything you buy, taxes will deny; I’ll Wesley Snipe your ass before thirty-five” (Duckworth et al., 2015).

Given that the racially-biased institutions of education largely control the influx of individuals who receive educational opportunities, African-Americans have been historically disenfranchised from academic enrichment. The double-entendre use of Wesley Snipes serves to reference the aforementioned case of tax evasion and the tendency for Uncle Sam to target young and prosperous African Americans. Duckworth emphasizes that regardless of the fame a young black individual like himself may reach, financial institutions will attempt to bring them down from success.

However, amidst the negativity of systemic racism, Duckworth implies that black individuals should embrace their own identity, especially with respect to their African-American culture. The theme of the track implies that although it is significantly more strenuous for black Americans to achieve prosperity, it is possible with a mindset that emphasizes self-assurance and social consciousness.

In the context of the album it belongs to, “Wesley’s Theory” effectively illustrates elements of the African-American experience, especially in regard to the integration of classism and racism in the modern structure of American society. The inclusion of historical themes relating to slavery and Reconstruction provide the song with additional merit, given the rarity of history being explored in modern mainstream music. Duckworth integrates a compelling and personal point of view to address these issues in an overarching narrative, which ultimately illuminates a window of hope for individuals subjected to violent oppression.

References

Duckworth, K.L., Clinton, G.E., Ellison, S., Colson, R., Bruner, S.L., Gardiner, B. (2015). Wesley’s theory. On To pimp a butterfly [CD] Carson, CA: Top Dawg Entertainment.