Protecting LGBTQ+ equality from Christianity—with Christianity

PHOTO BY ADAM KIRCHOFF

Churches flying LGBTQ+ pride banners and social justice flags are few and far between. Some Christian churches in California shamelessly denounce any concept tied to leftist ideas. Others might excuse their neutral stance as an attempt to avoid division. Indeed, politics and religion should not be bound together. A separation between church and state assures the freedom of religion in this country and prevents any real notions of theocracy. But glancing at the recent history of homophobia in California reveals an overwhelming tie to Christian ideologies.

This might seem like a statement of the obvious, but the relationship between religion and the LGBTQ+ community is complex. Christian teachings generally promote a sense of unity through the Bible, encouraging followers to “love thy neighbors,” regardless of identity. Yet, many people in religious circles view gay, trans, or any queer lifestyles as intrinsically immoral. They tend to subscribe to zero-sum beliefs, perceiving any queer rights progress as an attack on their religious identity.

For both the LGBTQ+ community and non-LGBTQ+ allies, this history of queer erasure clouds their willingness to affiliate with the Christian following. This creates an especially intense dilemma of cognitive dissonance for those who want to maintain their religious faith without denying their own sexual preferences or gender identities. Some mask their identity from their religious families to avoid conflict; others endure abuse and rejection upon “coming out.”

The teachings at the First United Methodist Church in Sacramento, however, offer solutions to this debilitating social conflict. The church sits in the eclectic community of midtown Sac, adorned with a series of heart-shaped, rainbow-colored banners. Adjacent is a Black Lives Matter flag and a neighboring message: “God speaks through the queer and trans.” It presents itself as an LGBTQ+ affirming place of faith, striving to thwart the barrage of judgment that other Christian churches often foist on their congregations.

Their leadership is committed to fostering a welcoming environment “for persons of all sexual and affectional orientations and gender identities,” according to the church’s mission statement. And despite coming under the umbrella of Christian denominations, they separate themselves from the hateful ideologies that live in fundamentalist schools of thought.

The church’s lead pastor, Reverend Rod Brayfindley, sees religious anti-LGBTQ+ beliefs as a case of questionable interpretation and complex cherry-picking. He maintains the viewpoint that “a more biblical Christianity is going to be in the business of loving people and not judging people.”

“What I think you’re mostly dealing with is people who may be from a culture or life experience that want to feel negative about certain groups,” Rev. Brayfindley says. “They are going to search their Bible to find a way to judge those groups and justify a reason to not love someone.”

PHOTO BY ADAM KIRCHOFF

The United Methodist Church denomination controversially split in 2020 as a result of this dispute over

LGBTQ+ issues, particularly over whether gay or queer individuals could join the clergy or be married in the church.

Rev. Brayfindley, who has spent 39 years as a pastor for the United Methodist Church, and six at the Sacramento sanctuary, asserts that this loss of love for LGBTQ+ people contradicts the authentic vision of Christianity. He argues that “The critical issue is when people have already made a decision and look to the Bible to justify their decision.”

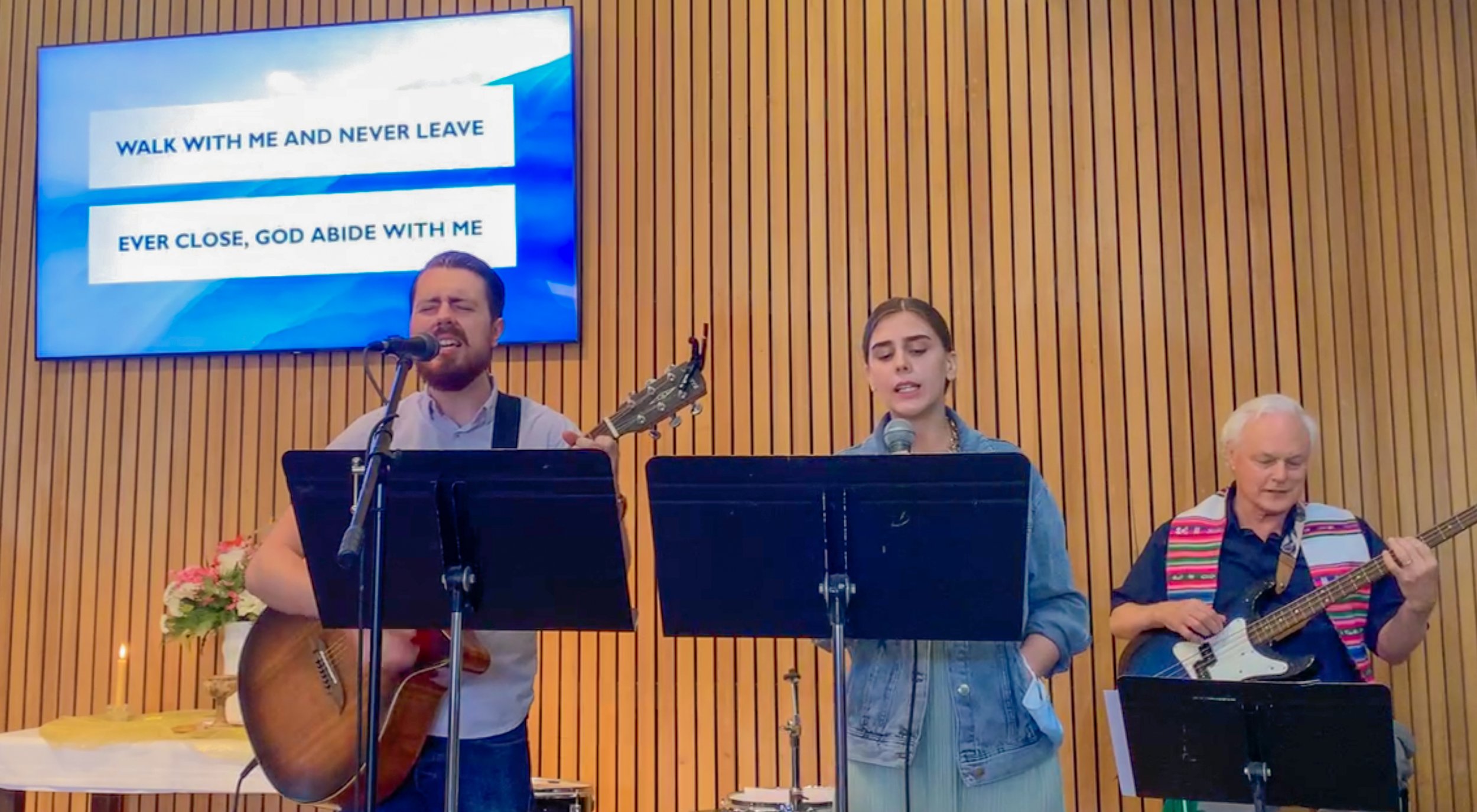

Celia Creasman and fiancé Broc Mason started attending First United Methodist in 2021 and soon started leading the contemporary church band that complements Sunday’s sermons. “They were really affirming and open, and aligned with our views, which is pretty rare for a church,” said Mason, who also now serves as the church’s communications director. “We were wrestling with our faith because of [how other churches dealt with] COVID and the [Black Lives Matter] protests [...], and we just could not stand with that anymore.”

“We meet a lot of people who think like us but have put organized religion behind them because they were unable to find a church like we did,” said Creasman. She says that the pride flags initially drew her and her fiancé to the church, but the leadership’s openness and action kept them there. Previously, Creasman only saw action coming from a church when it solely helped uphold their pristine image of Sunday service.

The First United Methodist Church furthers its cause by practicing what they preach, “whether or not service is going well,” Creasman said. “They work a lot with city council [to combat homelessness]. A lot of non-denominational organizations and non-profits will work here. We have LGBTQ+ book clubs and support groups that meet here and aren’t even part of the church. And it’s not an all-white, all-cis congregation who says they support queer rights. People in leadership are [of LGBTQ+ identities]. I’ve never experienced that before.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF FIRST UNITED METHODIST CHURCH, SACRAMENTO

Mason, Creasman, and Rev. Brayfindley performing before the congregation at a Sunday service

“I had never seen a church that big and loud [in their message],” she mentioned. “[Pastor Brayfindley] says something every Sunday to reassure everyone what the church stands

for. He also specifically tries to bring up whatever was happening that week that may have been challenging for society.”

Mason, Creasman, and Rev. Brayfindley performing before the congregation at a Sunday service. Creasman grew up in California as the daughter of a Nazarene pastor and always wondered why her church refused to discuss monumental shifts in the world. “Trump got elected, and my dad would talk about it at home but not say it out on Sunday. But then I realized it’s because not everyone [in the church] agrees.”

Currently, social media fanfare dominates the political climate. Brash identity politics— ignited by the likes of former President Trump and his cast of attention-seeking supporters in public office—have emboldened extremists. As a result, far-right camps— white supremacist coalitions, vaccine conspiracy movements, anti-mask crowds—have increasingly surfaced throughout even a solidly liberal California. But in a state where 47 percent of voters are registered Democrats, such inflammatory convictions will rarely, if ever, see the light of day on a state election ballot.

California’s progressive voting trends shape much of the state’s social infrastructure. Because of its reputation as an inclusive social sanctuary, many residents of California moved here to escape the confines of conservative states and their discriminatory policies.

Florida’s recently controversial Parental Rights in Education Act—perhaps better known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill—prohibits public school teachers from instructing on sexual orientation or gender identity in the classroom. In April, Tennessee’s state legislature proposed a bill (SB 2777) that permits public school teachers to misgender their transgender students. And lawmakers in Texas recently launched initiatives that would restrict transgender adolescents from accessing gender-affirming medical care, according to the New York Times.

As these relentless efforts to “other” the LGBTQ+ community pick up steam around the country, LGBTQ+ Californians grow wary. They fear that homophobia will cascade into their beloved Golden State, despite its tapestry of forward-thinking values. For despite being touted as the quintessential land for progressive social beliefs, California is no stranger to threatening homophobic discrimination. In Los Angeles County—the state’s most populous—hate crimes based on sexual orientation increased nearly 20 percent between 2019 and 2020, with 72 percent of those crimes being of a violent nature. Throughout the state, violent hate crimes against transgender persons increased by 64 percent in 2019 compared to the year before, according to a 2020 Hate Crime Report conducted by the L.A. County Commission on Human Relations.

As recently as 2008—just seven years before the U.S. Supreme Court legalized gay marriage in all 50 states—a majority of Californians disapproved of gay marriage and voted to ban it statewide through the passage of Proposition 8. Christian religious groups were perhaps the most notable proponents of the state amendment, with 88 percent of white evangelical Christians supporting the ballot measure and accounting for a majority of approval votes, according to the Public Religion Research Institute. In contrast, 80 percent of California voters without any religious affiliation opposed Prop 8 —exhibiting the control that Christian teachings have over the perception of LGBTQ+ lifestyles, per a survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute.

Just preceding the 2008 election, prominent evangelical leader Chuck Colson equated the legalization of gay marriage to Armageddon. He warned Christian followers that the event would mark the end of religious freedom in the country, which greatly assisted in the passage of the proposition. Prop 8 was later overturned, in 2010, after the U.S. District Court ruled that the amendment violated the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Views on non-heterosexual relationships have since shifted among the majority, with approximately 71 percent of Californians supporting gay marriage as of 2021, per the Public Religion Research Institute. Still, many of those bigoted attitudes linger within many religious communities. Megachurches—extremely large and conservative Protestant congregations—are a stronghold for reactionary social movements. California currently houses more megachurches than any state in the country, giving Colson-like queer erasure a sustainable platform.

PHOTO: ADAM KIRCHOFF

Church member Alexander Hayden exits the church after a Sunday morning service

“The LGBTQ+ people in our church have been in churches that spent lots of time condemning their whole nature, usually as young people,” Rev. Brayfindley recounts. “There is one person here who would sometimes lay down and cry after a church service because they had been in a church as a youth that had so rigorously condemned them. And to be in a place of welcome was overwhelming.”

“As LGBTQ individuals, it’s easy to get pushed away from God and spirituality,” congregation member Scott Stroman said. “Most churches aren’t welcoming, which starts to teach you that you’re not worthy of God. In my heart, I didn’t believe that—we look for churches to help build us up.”

So when Scott and Wyatt Stroman first came to First United Methodist, they were welcomed as members with a giant group hug. “This has been the first [religious] community where I felt like I belonged,” said Wyatt Stroman. “Our welcoming event was amazing. Of course, I was crying during the whole experience—and I’ll definitely never forget it.”

As this nationwide attack on LGBTQ+ rights gains more traction, California continues to establish itself as a place of refuge for gay, trans, and queer people to receive the care and respect they deserve. And with a reframing of Christian beliefs, perhaps that kind of respect won’t be negated by faith.

PHOTO COURTESY OF FIRST UNITED METHODIST CHURCH, SACRAMENTO

Rev. Rod Brayfindley—donning an LGBTQ+ pride clergy stole—ends his sermon with a communion

“I have a sister-in-law who is [gender transitioning], and she’s from the Nazarene church,” Creasman noted. “She still has her faith in Christ, but she doesn’t want to affiliate with any church organization, which I get. But now, I’ve been able to tell her that not all churches are like this. I’m more encouraged to think that there are like-minded people and congregations out there.”

“A lot of churches are like islands,” nine-year church member Alexander Hayden expressed. “Outside of Sunday, you don’t know they exist, but this church is involved. I really believe we serve God by serving humanity, and they really do that here.”

The First United Methodist Church of Sacramento challenges destructive beliefs that bring the state and country backward. California serves as an exporter of many sociopolitical trends observed throughout the United States. If other institutions

throughout the state —not just churches— follow suit with similar visions of empathy and inclusion, perhaps we can not just accept LGBTQ+ identities throughout the country but collectively empower and celebrate them.

“There are many welcoming churches in this town [...] we just happen to be on a corner where we can shout it out loud with our banners,” Rev. Brayfindley proclaims. “And we do.”